Title

"Justice is better than chivalry if we cannot have both"

In principle, nobiliary law should govern matters such as inheritance of titles, but varying practices in different regions create difficulties. In the Two Sicilies, for example, succession through female lines was not unknown, but in the Kingdom of Italy, where it was not automatic, a decree or descript was necessary to permit it. Today, the heirs to the kings are reluctant to issue decrees in matters of this kind.

Examples of some of the more important issues regulated by nobiliary law are:Claims to nobility (surname, coat of arms, title) by non-noble persons. This could, but must not, include: children with one or two noble parents but born out of wedlock; stepchildren to noble parents; children to a noble lady in an agnatic family, etc.

- Claims to nobility by noble persons, where the claims cannot be automatically verified. This could be e.g. the inheritance of a noble title in a junior line of the family when the senior line becomes extinct.

- Borderline cases, such as which among the ancient patrician families were, and were not, to be numbered among the nobility. Or the reactivation of a family's nobility after some time of voluntary or involuntary loss of nobility

- The naturalization of foreign nobility, which is the assimilation of immigrant nobility into the domestic nobility, usually with the purpose of ensuring the foreign nobility the same privileges as the domestic.

- Heraldry, and more specifically the use of certain symbols usually reserved for the nobility, such as coronets of nobiliary rank, the use of supporters, etc. Also marshaling of arms, that is the proper combination of two or more coats of arms due to marriage between two noble families, and similar issues may be regulated.

In some countries the nobility is a subject of public law (Belgium, Finland, Netherlands, and in Spain only regarding the titled nobility). In other countries this is not the case, and then the nobility may have organized itself in one or more associations in order to have an institution to handle nobiliary issues such as those mentioned above. It is therefore of the utmost importance for every noble family to define and clarify under which legislation, or under which set of rules or regulations whether codified or not, they are a subject.

Nobiliary law is a complex and multi-faceted subject. It is often necessary to do extensive research in order to establish which rules apply to a specific noble family. A starting place can be to collect relevant literature from (or about) the country where the family is known or believed to have been ennobled or first recognized as noble.

See Institution dedicated to nobiliary law such as the Italian http://www.dirittonobiliare.com/)

Perhaps the most important thing to remember about nobiliary law is that it is not the same as public law. It may well be possible, according to national legislation, for a non-noble person to assume a noble surname, but this does not make them members of the nobility. A person can only be a member of the nobility if they are so according to nobiliary law, whether this is in harmony with the public law or not.

In recent years the question of the legitimacy of international law has been discussed quite intensively. Such questions are, for example, whether international law lacks legitimacy in general; whether international law or a part of it has yielded to the facts of power; whether adherence to international legal commitments should be subordinated to self-defined national interests; whether international law or particular rules of it "such as the prohibition of the use of armed force" have lost their ability to induce compliance (compliance pull); and what is the relevance of non-enforcement or failure to obey for the legitimacy of that particular international norm?

(Legitimacy in International Law Series: Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht , Vol. 194)

Authors Nico Krisch and Benedict Kingsbury argue that international governance has become increasingly administrative. The international legal order has changed. It is no longer adequate to think of the international legal order in terms of inter-state, consent based law. In the classic notion of international law, norms are agreed upon by states, and states were free to accept or reject these laws. In order to be effective, international laws needed to be ratified and implemented at the domestic level.

The basis for the legitimacy of international law is changing.

International law used to be considered legitimate when it rested on the agreement of sovereign states. Domestically, however, states were free to organize institutions as they saw fit. However, it has become less important for states to ratify and implement international law. Domestic institutions are subject to international regulations that they did not officially agree to.

International law comes from new sources.

International regulation now flows from sources other than states. Sources like public-private or even purely private institutions now serve to create global law. Additionally, international judicial bodies define and extend international law. At one time, international regulation generally counted as ?formal law? when it originated in agreements among states. However, it no longer makes sense to limit the term ?law? to formal state agreements or widespread conventional practices. Increasingly, non-state actors are involved in coordinating and regulating global activity.

"It should also be clear that, whereas national laws aim to provide clear-cut definitions or criteria, their validity extends only to their own borders. One country may well be indifferent to, or even recognize, what another calls bogus. A case in point is the various orders of Saint John recognized by their national governments (Britain, Germany, Netherlands) but not by others (France) or, until the early 1960s, by the Catholic Order itself". http://www.heraldica.org/topics/orders/legitim.htm

International law comes from four sources:

(1) treaties and agreements;

(2) customary law;

(3)general principles of law common to major legal systems; and

(4) judicial decisions and scholarly teachings.

Treaties and customary law have equal authority as international law. If they conflict, the ?last in time? rule operates, meaning that whichever came into force most recently takes precedence. When treaties and customary law are not helpful, one may then consult general principles, which most frequently come into play to determine procedural matters. If an issue cannot be resolved after examining these sources, decision makers should then consult scholarly articles and judicial opinions.

However, overburdened judges often rely on scholarly works as definitive evidence of customary international law or general principles instead of conducting independent assessments of primary sources.

Customary Interntional Humanitarian Law

Addresses customary international law, and specifically, customary IHL. Customary law is "international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law" resulting from a general and consistent practice of states followed by them from a sense of legal obligation. Thus, a principle is considered customary law if many states across the world feel legally obliged to follow that principle. This sense of legal obligation is commonly referred to as opinio juris.

Traditionally, customary law is meant to reflect the world as it actually exists and is not intended to reflect aspirations or ideals. Knowing that international and domestic judges are likely to treat this listing similarly to the way American judges treat restatements of common law.

(RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES

§ 102 (1987) (recognizing as sources of international law treaties and agreements; customary law; and general principles of law); see Statute of the International Court of Justice art. 38, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, 1060, T.S. No. 993 (recognizing that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) can use ?judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations? to decide disputes).

There are a plethora of multilateral treaties which address the issue of IHL, but not all states are parties to every treaty and a majority of the treaties only pertain to international conflict. The division between international and non-international conflict dates to the Geneva Conventions, some of the few treaties to which every state is a party. The Geneva Conventions, with the exception of the very vague and general Common Article, only apply to international conflict.

(Geneva Conventions consist of four treaties formulated in Geneva, Switzerland, that set the standards for international law for humanitarian concerns. These four treaties are the basis for humanitarian law across the world). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geneva_Conventions)

Signing of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864.

The legal basis of titles and honors

In

the UK, titles and honors are not merely matters of social convention.

There is, for example, a defined procedure for determining whether

somebody is a baronet, and a correct answer to whether a member of one

Order of Chivalry takes social precedence over a member of another.

These issues are determined by what is known as nobiliary law.

Questions of nobiliary law may be difficult to answer, particularly

because some rulings are of great antiquity and not easy to follow.

However, they are, for the most part, questions which do have definite

answers which can be researched, rather than matters of social

preference.

On

the whole, nobiliary law is not to be found in statute. Although there

is a small body of statute law which applies to titles and honors, the

creation, recognition, and grant of titles of honor is technically one

of the prerogative powers of the Crown. Prerogative powers are

the vestiges of the archaic powers of the monarch to rule by

proclamation, rather by the procedures of Parliament. In practice, the

exercise of prerogative powers is now by `the Crown', which is that

uniquely English constitutional phenomenon in which the monarch acts on

the "instructions" of the Government of the day. So, in practice, new

titles are conferred by the Queen or by the Prime Minister of the day.

In theory, it lies in the power of the Crown to create not just new

title-holders, but whole new titles. This has happened in the past, of

course -- in the immediate post-Conquest era there was only the rank of

baron; all the other classes of peerage are more recent creations.

Regulations

governing titles and honors are usually formally instituted by letters

patent or royal warrant, signed by the monarch, and in many cases

countersigned by a minister to indicate that ministerial advice has been

given.

One

statute that is important is the Honors (Prevention of Abuse) Act

(1925). This Act makes it a criminal offence to offer, or to accept,

money or other reward to obtain the grant of a dignity or title of

honor. In the medieval past, however, there is no doubt that noble

status was attendant on wealth, particularly in the form of land. A

person who had acquired a sufficiently large estate could petition the

monarch for a peerage. In practice, Prime Ministers do reward their

long-term supporters with honors and peerages, and this support may take

the form of money.

Although peerages cannot be bought or sold in the UK, titles of nobility may have been salable in other jurisdictions. You may sometimes come across people offering to sell French and German titles. Apart from pointing out that these titles would confer no particular status in English law. Of course, since the reform of the House of Lords a hereditary English peerage probably carries no more extensive legal rights in the UK than does a hereditary French one.

What is « fons honorum » ?

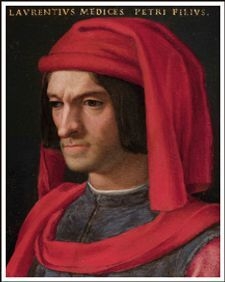

Picture: Lorenzo il Magnifico ("the Magnificent"), Piero il Gottoso's older son (1449-1492) Florence's leading position was consolidated under Lorenzo)

In practice the « ius honorum » (right to grant honors, notably nobility) is materialized in a « fons honorum

». In the monarchies it?s confided to the Sovereign on hereditary

basis, as emperor, king, prince, grand duke, etc? In case of deposition,

the deposed sovereign or a pretender to the throne who succeeds him by

hereditary right (ius sanguinis) stays possessor of fons honorum. Although in general unknown, presidents of republics are also possessors of fons honorum

for the time of their mandate. In the officially democratic systems of

government, it is the people themselves who are truly sovereign and who

possess ius honorum, the right to grant honours which are granted in their name by a fons honorum which is confided to a constitutional sovereign or a president of a republic.

What is "fons honorum" (fount of honor ? right to grant honors)? The extent and contents of fons honorum (according to particular traditions, epochs, places and customs, include honorary distinctions of merit or other titles. This encompasses orders of knighthood, nobility, titles of nobility linked or not to a peerage, noble titles devoid of nobility stricto sensu, recognized coat of arms, etc?

The Sovereign was and is the first and most exclusive right and honor (quod principi placuit legis habet valorem), and all highest powers are centered in this figure. These are also called the ?prerogatives of the crown? and can be summarized as follows:

a) Jus imperii, i.e. power of command;

b) Jus gladii, i.e., right to obedience by his subjects;

c) Jus majestatis, i.e., right to receive defence and honors;

d) Jus honorum, i.e., right to award, grant honors, noble and knightly dignities, or to invest others with the power to grant said honors.

In

current public law, sovereignty lies with the State or, as we all know,

with the people legally organized to govern a land. By saying people,

we mean ?all? the people, in the same way it is organized in nature with

the various classes being distinct from each other, each one formed of

groups of similar, able or unable, gregarious or leaders, favored or

frowned upon by fortune or society.

The

concession of a noble title in Italy is not a prerogative of the State

today, but is for virtue of the merits recognized of the person by the

prerogatives and discretion of the pretender prince to the throne.

The recognition is granted to people who have distinguished themselves for their actions in favor of the Sovereign House, for independent valorous or charitable deeds, and for the recognition of private or public good deeds, which have touched the sensitivity of the Pretender Prince, and do not depend on the relationships with the public or the country the person belongs to.

This concept has always been taken on by the ex-reigning Houses who have lost their throne further to final occupation of the territory: in this case, as the situation of debellatio is not applied, the figure of the Pretender Prince to the throne has emerged.

The Sovereign abandons the country, but he does not lose his rights to sovereignty, or to be precise, he conserves intact certain prerogatives, which he can still exercise, while others are suspended. Without doubt, among the prerogatives he conserves intact there is Jus honorum, the right to grant noble titles and honors in knightly orders that are part of the wealth of the Crown.

If a current noble title is deserved and born well, it is equal to those received in past centuries, as anything is current in the moment it is acquired: this noble title is emanated by the Sovereign prerogative (rex nobilem tantum facere potest), and the Sovereign is in the position of an "object" faced with a "subject"; therefore the noble title does not have ?antique? origins but "dative". Its use and transmission are governed by the investiture deed through the "Letters Patent".

Therefore a Princely House, previously Sovereign, is always considered a Dynasty and the current Head of Name and Arms conserves the titles, prerogatives, and dues of the last dethroned sovereign, with the name of Pretender Prince, previously Royal Highness, Imperial Highness, or Serene Highness.

In the XIV transitory disposition of the Italian Constitution, noble titles have never been abolished, simply they are not recognized, but the fact they are not recognized just means that republicans are not interested in titles, that they are private wealth before being historic. The Constitutional Assembly could not deprive citizens of an inborn right, because it would be the same as if a law were approved in the future that cancelled certain surnames.

Therefore the ordinary Magistracy is the only authority which, regarding the safeguard of the most jealously kept and delicate of human rights ? our name ? has the task and power to ascertain the legal noble status of a person, and declare the right to include the status in the surname, as established by the XIV transitory and final disposition of the Constitutional Decree.

The

International Arbitration Tribunal, established under Italian and

International law, issues a sentence ascertaining the right to noble

titles, predicates and legitimacy of the noble coat of arms.

The sentence issued by the International Arbitration Tribunal is a first-degree sentence under Italian law, once an execution decree has been issued by the President of an ordinary tribunal, pursuant to art. 825 of the Italian Civil Procedure Code. The extract of the sentence and the decree by the president of the ordinary tribunal are published in the Official Gazette.

This sentence is irrevocable under Italian Law, and can be executed, within the limits established by international law, within those States that signed the New York Convention on 10th June 1958. Likewise the sentence establishes that on the confirmation and baptism certificates, the title and predicate can be included.

A

noble who wishes to freely use his title, has no need to be recognized

and, less still, to be registered in the Gold Book or other "Official"

Lists of Italian nobility. The fact the person is not registered does

not mean he cannot continue to use his title, as long as it is true,

thus reaching a clear distinction between "existing title" and "recognized title".

What counts is the effective concession of the title and legal possession by the person or family; possession which must be proved by historic, genealogical, legal and canon documentation. The person must possess the appointment deed (letters patent and decree) that proves the claimed right to nobility, so that he does not need to be recognized and, less still, to be registered in the various lists.

Noble titles granted by the Head of Name and Arms of a Dynasty, to be received and born, do not require any registration in the registers of the ex Heraldic Consulta, nor in the various Official Lists, or lists in the current Gold Books held by private associations (The Heraldic Council), as those noted pursuant to the Order of the Italian Nobiliary State refer exclusively to titles granted or recognized by the Savoy Family and subsequently those by the Vatican, recognized further to the Agreement of 11th February 1929.

Picture above left: Napoléon Bonaparte French General, First Consul and Emperor, b. 15 August 1769 (Ajaccio (Corsica), France), d. 5 May 1821 (St. Helena Island). Napoleon's father Carlo Buonaparte and his mother Letizia Ramolino came from ancient nobility of the Italian region of Tuscany. The family had emigrated to Corsica in the 16th century, when the island was under the control of the Italian city-state of Genoa.

To conclude:

"a) Nobility is the only emanation of Royal, Imperial and Serene prerogative and to be more precise, Sovereign;

b) Once a noble title has been acquired with relative predicate and

arms, it is not lost if it is not used or a term lapses, as it is a part

of the unavoidable wealth of the person;

c) the predicate should be an integral part of the surname;

d) "Noble Titles" should not be confused with the ?Sovereign Titles?,

even if their qualification (e.g. Prince) could be the same, and we must

remember that the former are subject to special regulations (regarding

their recognition, succession, etc.), the latter do not require any

formalities, as they are native.

This way the concept of nobility, today without any conceit or privilege, becomes part of sociology as a refinement of the human race in its continued future, with the aim of holding high the banner of the country?s history, which is the symbol of respect for traditions, undeniable life force and source of energy in any evolution of time, society and institutions".

Source: (Consiglio Araldico Italiano - Istituto M.se Vittorio Spreti

Piazzale Stazione, 6 - 35131 Padova / Italia).

Professor Emilio Furno, an advocate in the Supreme Court of Appeal, writes as follows ("The Legitimacy of Non-National Orders", Rivista Penale, No.1, January 1961, pp. 46-70):

"There are not a few judgments, civil and criminal, albeit some very recent, all of which tend as a rule to the acceptance of traditional principles re-enunciated not long since. The issue is that of innate nobility - Jure sanguinis - which looks into the prerogatives known as jus majestatis and jus honorum and which argues that the holder of such prerogatives is a subject of international law with all the logical consequences of that situation. That is to say, a deposed Sovereign may legitimately confer titles of nobility, with or without predicates, and the honorifics which pertain to his heraldic patrimony as head of his dynasty.

The qualities which render a deposed Sovereign a subject of international law are undeniable and in fact constitute an absolute personal right of which the subject may never divest himself and which needs no ratification or recognition on the part of any other authority whatsoever. A reigning Sovereign or Head of State may use the term recognition in order to demonstrate the existence of such a right, but the term would be a mere declaration and not a constitutive act".

A notable example of this principle is that of the People's Republic of China which for a considerable time was not recognized and therefore not admitted to the United Nations, but which nonetheless continued to exercise its functions as a sovereign state through both its internal and external organs.

"The

prerogatives which we are examining may be denied and a sovereign state

within the limits of its own sphere of influence may prevent the

exercise by a deposed Sovereign of his rights in the same way as it may

paralyze the use of any right not provided in its own legislation.

However such negating action does not go to the existence of such a

right and bears only on its exercise »(Furno, op.cit.) The eminent

author concludes: « To sum up, therefore, the Italian judiciary, in

those cases submitted to its jurisdiction, has confirmed the

prerogatives jure sanguinis of a dethroned Sovereign without any

vitiation of its effects, whereby in consequence it has explicitly

recognized the right to confer titles of nobility and other honorifics

relative to his dynastic heraldic patrimony. In particular it has

defined the above-mentioned honorifics, among which are those

non-national Orders mentioned in Article 7 of the (Italian) Law of the

3rd. March 1951 which prohibits private persons from conferring honors.

As to titles of nobility, while their bestowal is legitimate, it must be

observed that they receive no protection whatsoever from Italian law,

which no longer recognizes statutory nobility, in accordance with the

principles enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic. Thus, the

concept of the usurpation of a nobiliary title falls outside of Italian

legislation.

(op.cit.)"

To the superficial objection that involved transmission through a female line (as also in the case of the title of Prince of Emmanuel) it may be replied (cf. V. Powell-Smith: In the Matter of the Sovereign Order of New Aragon and in the Matter of the Government of Antigua and Barbuda, Submission, 1982) that the Salic Law did not run in Aragon and that thus succession could be through a female line and that the same applies to Sicily (G. Galuppi: The Present State of the Nobility of Messina, Milan, 188 I, pp. 1 -23). This is also shown by the Constitutions In Aliquibus of King Federico II of Sicily which admitted succession in the female line (Constitutiones Regni Sicilae, liber 3, tit.26).

I

t

is undeniable that the Salic Law applied generally in the Kingdom of

the Two Sicilies, but as far as Sicily was concerned its application was

subject to the traditional limitations, even under the Bourbon dynasty.

Further evidence of this is given in the express recommendations of the

Royal Commission on Titles of Nobility (2nd February 1860) and in the

Decree of King Francesco II of the Two Sicilies (16th September 1860)

both of which support the transmission in the female line of the title

of Prince of Emmanuel.

Georgian

succession laws are not Salic. Women did rule more than once, in fact,

one of the greatest heroes and sovereigns in our history was a woman.

King of Kings (Queen of Queens) Tamara is celebrated as one of great

people of our land. The rule of succession in the Bagrationi dynasty is

similar to that of Byzantium, according to which the royal throne could

be transferred not only to the eldest son, but also to the youngest one.

In the absence of a male heir, the throne of Georgia could then pass to

the eldest daughter. When a Georgian female heir-to-the-throne got

married, the Georgian Dynastic Law of ?Zedsidzeoba? ("Georgian Law on

marriage concerning" Consort son-in-law?), was applied (see D. Ninidze "Offshoots of the Bagrationi Royal House in the 16th-18th centuries",

Tbilisi, 2004, p. 41). According to succession law, if a princess of the

royal blood marries a noble, he would be recognized solely as the Prince consort and the children become nobles rather than royals.

It is a general principle of nobiliary law that the head of a dynasty which formerly reigned retains jure sanguinis, that is by hereditary right, the faculty of conferring chivalric and nobiliary honours, known as the jus honorum (in the act of so conferring them he is called fons honorum, fount of honours) and retains his sovereign rights irrespective of political changes or territorial considerations. These rights are called rights of pretension from which arises the term Pretender, which indicates that he maintains and / or exercises those rights and enjoys them in perpetuity (cf. Renato de Francesco: The Legitimacy and Validity in Italy of Non-National Chivalric Orders, ed. Ferrari, Rome, p.10).

According to Salvioli (History of Italian Law, Utet, 1930, p.272) sovereignty as an element of state power sprang from the struggle of the kings against the great feudatories and owes its character of necessity to the resulting concentration of the powers of the state in the hands of the monarch. « Born of feudal origins, this power continued to bear the imprint of the personal property of the Prince, whence derives its transmissibility by hereditary right in perpetuity ». By this doctrine the Prince logically retains his sovereignty always (suprema potestas, whence supremitas, sovereignty) even when he is no longer reigning.

Since all power is thus centered in the sovereign, he possesses the political authority, jus imperii, the civil and military power, jus gladii, the right to respect and to the honours of his rank, jus majestatis, and finally the right to confer honors and privileges, jus honorum (G.B. Ugo, Bascap¨, Gorino-Causa, Nasalli Rocca, Zeininger and de Francesco).

A sovereign, whether actually reigning or a Pretender, may not only confer in particular his dynastic Orders, but may also create new ones and revive those which were founded by his ancestors (this principle has been determined by the Italian Supreme Court of Appeal) without taking into consideration the fact that by the vicissitudes of succession or of politics some of those Orders may have passed in to the hands of another dynasty.

The Italian Law of 1953 admits the existence of non-national Orders and distinguishes them from State Orders, as being conferred by other than private societies or associations. With the exception of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, we may broadly speaking identify two types and say that non-statutory Orders are none other than non-national Orders. Among the latter we may disregard the capitulary Orders which elect their own Grand Masters and we may concentrate upon those which have been founded by dynasties, which may not in fact be now reigning. According to the above-mentioned Law, such Orders are legitimately conferred and as such valid.

Prof. V. Powell-Smith writes (Submission cit. and « The Criteria for Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry « « Nobilitas », Malta, 1970):

...there is no valid reason, legal or historical, to define Sovereign status by reference to 1814 or any date at all. The Congress of Vienna merely effected the settlement of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, and nothing more. Changes in the political structure of Europe have occurred since the Congress of Vienna: for example, the establishment of the Balkan kingdoms and the unification of Italy and the sovereigns of these kingdoms acted as fontes honorum. The purpose of the Congress of Vienna was to reorganize the territorial boundaries of European states. Certain states, the existence of which had been effectively terminated the by Napoleonic settlement were not re-established but were integrated into larger units, the sovereign princes willingly accepting such an arrangement which retained their rights as princes but removed their former territorial rights (the case being of numerous small German principalities). The rights of fontes honorum not represented or discussed at the Congress (because they had no interest in its decisions which related to de facto territorial adjustments) could not have been affected by what was decided at the Congress or later arguments ex silentio on the question.

It is clear that the concept of sovereignty may have different applications in reference to the sovereignty of a modern state as distinct from that of a Pretender. Generally speaking the sovereignty of a state is exercised within the ambit of a definite territory, upon a population (either the subjects of an absolute monarchy or the citizens of a republic) in an international context. In the case of a Pretender his sovereignty is exercised neither within the ambit of a territory nor upon a population nor in an international context.

The absence of a territory is not a determining factor; its possession is in fact subject to political vicissitudes, which have no bearing on the rights and the legitimacy of the pretension of a Pretender. In his case the concept of a population of subjects is replaced by that of the supporters who, by one means or another, uphold his cause. The international context is subject to political assessments and to the relative policies of governments, which in a changed view of the state (the will of the people has replaced the divine right of sovereigns) do not recognize the pretensions of once reigning Sovereign Houses unless they enter into the perspectives of the pursuit of the well defined ends of international politics.

It

is clear that henceforth, as it has been for some time, modern states

will not recognize either Pretenders or non-national Orders of chivalry.

That does not mean to say in the case of many Orders or of formerly

reigning Sovereign Houses that they are condemned to a limbo of

parchment and tinsel.

Countries generally do what they wish to, in spite of international law. For example, a legal opinion written by Willliam P. Barr, assistant Attorney General on June 21, 1989, declared that the United States "has the power to override customary international law" in certain areas. This understanding that the US has unquestionable authority "to exercise the sovereign's right to override international law (including obligations created by treaty) has been repeatedly recognized by courts."

http://www.fas.org/irp/agency/doj/fbi/olc_override.pdf

Archbishop Hyginus E. Cardinale in his book stated:

"A Sovereign in exile and his legitimate successor and Head of the Family continue to enjoy the ius collationis [the right to confer and enjoy honours] and therefore may bestow [such] honours in full legitimacy. . . . No authority [no matter what that authority is] can deprive them of the right to confer honours, since this prerogative belongs to them as lawful personal property iure sanguinis [by right of blood], and both its possession and exercise are inviolable." (Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See --- A historical, juridical and practical Compendium, Van Duren Publishers, Gerrands Cross, 1983, p. 119)"

Although not an international court, the following legal conclusion reflects knowledge of perpetual sovereignty. The learned Italian judge officially recognized that:

"Among

those rights [of a former ruling house inherited by the successors is]

the faculty to ennoble, to grant and confirm coats of arms, to bestow

titles drawn from places over which their ancestors had exercised their

sovereign powers, and also the right to found, re-establish, reform and

exercise the Grand Magistracy of the Orders of Chivalry conferred by

their family, which may be handed down from father to son as an

irrepressible [or unending] birthright." (The United Court of Bari, The Republic of Italy, Sig. Dr. Giovanni de Gioca, March 13, 1952:

http://www.mocterranordica.org/BariEng.pdf

PUBLIC OR PRIVATE "FONS HONORUM"

In actual practice in the XXIth century there exist several classes of public or private « fons honorum » with an extent more or less important according their legality or their legitimacy. Let us examine the prerogatives of fons honorum only from the point of view of a right to grant nobility and titles of nobility :

-Fons honorum of first class : reigning sovereign of a State whose Constitution sanctions the power to ennoble and to confer a title, without ever granting special privileges to those entitled in democracy.

-Fons honorum of 2d class : a deposed sovereign after a change of constitution or revolution etc.without abdication.

-Fons honorum of 3d class or private fons honorum: whereby a pretender to the succession to the throne of a State before 1814 (Congress of Vienna) under an absolute monarchy when the sovereigns, had a fons honorum iure sanguinis, or the pretender to a throne after 1814, heir to a deposed sovereign.

-Fons honorum of 4th class : an hereditary and aristocratic association or society, one or the other private or recognized (de jure or de facto) by the State when it?s a matter of a republic or a monarchy not foreseeing or no longer granting titles of nobility by the Head of the State and refuses to grant or allow foreign titles to its citizens, without specifically forbidding the granting of such titles by aristocratic groups within the country in the name of the people, who always implicitly possess the ius honorum that it delegates explicitly or implicitly, with or without recognition of the State. The level of legality and /or legitimacy is evidently linked to the national Constitution, at the status of Head of State : or of ancient monarch, or of pretender, or finally at the nature and content of the fons honorum. The Republic of the United States of America abstains to confer or recognize nobility and noble titles coming from foreign sovereigns or powers.

There was and there are still Republics conferring nobility and titles of nobility

The United States of America does not grant titles of nobility and limts citizens' ability to accept titles from abroad.

This Republic of San Marino has granted nobility and titles of nobility since the XVIIth century. Its fons honorum

emanates from the people of San Marino themselves represented by it?s

representatives in the Council of Sixty (or Grand General Council) which

is a higher expression of Executive Power.

This Sovereign Council confides its Fons Honorum to the two Captains Regents and the Congress of State said also the Council of the Twelve which is the Government. So the noble honors of San Marino come really from the nation. These titles of nobility are granted only to non-citizen foreigners for services rendered. They are symbolically attached to precise places, villages or towns of the territory without being linked to any property ownership. That resembles the British system of peerage, and to a lesser degree the French system, generally accompanied by a genuine property.

Now we find here below the American Constitutional basis.

The

American system of honors is relatively close to this model in many

aspects. First let us note that in the United States of America, the

Constitution completely denies to the nation state any rights to grant

titles of nobility and furthermore forbids its citizens from accepting

any titles of nobility from any foreign sovereigns or powers.

"The

article 1, section 9, clause 8 and 10 of the American Constitution

forbids to the United States (and evidently the states of the

Federation) to grant notably titles of nobility, and forbids also to the

American citizens holding public office from accepting or bearing such

titles coming from foreign sovereigns or powers except for the

permission of the Congress, which is never given. The sanction is heavy :

the loss of citizenship"

"A citizen granted foreign title may thus retain the title but will simply be forbidden from holding any position of authority in the US. The US Constitution does not ban American citizens from receiving titles of nobility from other countries, and one may be born into both. While there is a proposed Constitutional amendment currently pending that would more broadly revoke the citizenship of any person who accepts a foreign title of nobility, it has been pending since 1810"

The article 1, section 10, confirms: «No state shall grant any title of nobility.»

Now let us see an element of the legal doctrine:

«The TONA" (Titles of Nobility amendment) does not say anything about domestic titles of nobility- only those which might be issued by foreign powers. Even if it might be seriously contended that attorneys and others hold special « honours » or privileges by virtue of their positions, the language of this proposed amendment probably would not apply if such titles were to be issued by federal or states governments ». (Congress, and most state legislatures, are otherwise precluded from issuing domestic titles of nobility, as Article I, Section 9, clause 8 , of the original Constitution makes clear).

Let us examine the consequences. The article 1, section 9, clause 8 and 10 of the American Constitution forbids to the United States (and evidently the states of the Federation) to grant notably titles of nobility, and forbids also to the American citizens from accepting or bearing such titles coming from foreign sovereigns or powers except for the permission of the Congress, which is never given. The sanction is heavy : the loss of citizenship.

It is important to define with precision what we comprehend by «title of nobility». At the time «under the English law» the nobility is strictly defined and verifiable. As the Blackstone´s explanation in 1760, the usual noble titles in use were limited to duke, marquis, earl, viscount and baron. It?s significant to see the definition to exclude royal titles of king or prince as well as lower titles such as knight which are not hereditary. We see also, that the title of squire or esquire is excluded.

See Blackstone quoted by Carlton F.W. LARSON, Titles of nobility, Hereditary privilege, and the unconstitutionally of legacy presences in public school admissions , article in Washington Law Review, Vol.84, n°6, 2006, pp. 1376 -1440.